Posted in: 05/13/2021

On May 13, we celebrate 133 years since the Abolition of Slavery law in Brazil, the last country in the Americas to end slavery. But, just like other important dates for the black population in the country, such as Black Awareness Day, this is not a date for celebration either, especially for the quilombola communities.

Although it marks one of the most decisive moments in the history of the black population in Brazil, abolition put an end to slavery, it did not provide inclusion in society for these people. It was enacted without guaranteeing any kind of support so that these people would not remain trapped in the old exploitative relationships.

Historians even indicate that, in opposition to the idea of providing conditions for enslaved people to remain outside the domain of their former masters, many Brazilian farmers were already counting on the English orientation to make the end of the slavery model the beginning of a new model of servitude.

Thus, former masters would be exempted from paying for shelter and food, among other expenses, and freed people would end up subjecting themselves to the same type of service in exchange for tiny amounts of money that, in the end, would return to the hands of their own master.

In many cases, the exploitation relationship was maintained by the use of land, on which they had to work in exchange for housing, producing for the boss and leaving all, or almost all, the result of their labor in his hands. In others, the formerly enslaved people went to distant regions, but they didn’t find better conditions either. Thus, various other forms of servitude were created.

The lack of measures to include newly freed enslaved men and women reinforced the social abyss and the exclusion of a portion of society that would still take many years to begin to secure basic rights, such as political participation through voting or access to education, jobs, and better quality of life.

Even today, the creation of public policies, or affirmative action policies, that guarantee representativeness, proportionality, and respect for cultural and religious manifestations for the black population is a subject of struggle and debate. The lack of historical reparations still brings damage to society and, mainly, to the black population in Brazil and in the world.

As we have seen, the abolition process as it was done generated historical inequalities and still impacts society nowadays, mainly in the form of structural racism, which keeps control of the main decisions that affect society in the hands of majority white groups.

When we evaluate the data released about the black population and the main sectors in the country, it is easy to understand how structural racism works in Brazil:

Want to check out more information and get to know some of the fundamental topics to understand racism and the main issues faced by the black Brazilian population? Download the Synergia Anti-Racism Guide!

In it, you will learn more about structural racism and its consequences in society, representativeness and proportionality, standpoint of speech and careful listening to issues of black people, consumption and appropriation of black culture and standards of beauty, affirmative educational policies and quotas, and finally, about the educational process of becoming antiracist and fighting racism.

But how can we talk about the abolition of slavery and its relation to today’s data without talking about the quilombola peoples?

Some of the communities formed by enslaved people fleeing their masters, and which later also served as shelter for freed people, have endured over time. Quilombos are a symbol of confrontation and resistance.

As most of the communities were formed in places of difficult access, many became autonomous and started to live on subsistence, preserving their own traditions and cultural practices, as well as their strong relationship with the land.

Today, with even less visibility than the black population that lives in the big cities and has access to more resources, the remaining quilombola peoples have to fight hard for their relations with the land and their culture to be preserved.

According to IBGE estimates, in 2019 there were 5,972 quilombola localities in Brazil, in at least 24 states. Barreirinha (AM), with 167 localities tops the list of municipalities with the highest estimated number of localities. Pará concentrates the largest number of areas with official demarcation of quilombola lands: there are 75.

It is worth remembering that the 1988 constitution, as a measure of reparation, recognized access to land as an essential right for the quilombola communities that already inhabited it, giving them the right to its use and ownership.

According to the government’s official website, the data are subject to revision until the official publication of the next Census, planned for 2021, but still without an official date. This will be the first time that the population that considers itself quilombola will be identified by IBGE through the main demographic research of the country, since the previous Demographic Censuses did not contain questions about this part of the population.

It is noteworthy that we are talking about a portion of the black population that is even more excluded than the black Brazilian population in general. The IBGE’s delay in mapping data about these people is an example of this and of the lack of appreciation for the culture and existence of quilombolas in Brazil.

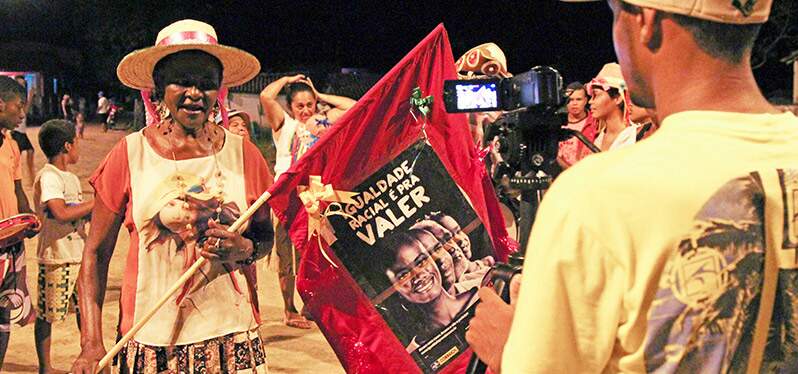

In 2014, Synergia had the opportunity to conduct the Ethnocultural Rescue and Identity and Cultural Practices Enhancement Program of the Quilombola Communities of Patioba, Terra Dura and Canta Galo, in the municipalities of Capela and Japaratuba, in Sergipe.

The aim was to rescue the quilombola culture in the region and strengthen the feeling of belonging to the community, promoting social development, and valuing the local traditional community. For months, we followed the routines of the residents, their festivals, cooking practices and use of medicinal plants, living habits, dances, and songs.

In one of the most interesting actions, the communities received training and audiovisual equipment so that these daily moments, so representative of the quilombola experiences, could be recorded by themselves. The set of materials, called Fios da Memória (Memory Threads), had a great impact and consolidated itself as a reference of the quilombola culture in Sergipe.

The immersion in the culture and in the daily life of the people demonstrated how necessary it is to establish public policies for the protection of rights and for these people not to lose their cultural identity and the traditions of the African matrix. It is necessary to reinforce that the quilombola peoples are part of society and need to have this place recognized, as well as their rights respected.

Sign up and receive our news.